Land Acknowledgement

The following Land Acknowledgements were approved by the ELAC Academic Senate, October 26, 2021.

For faculty and staff: Below are two versions of the Acknowledgement. They may be read or placed in syllabi, campus documents, event programs, etc. Feel free to replace "East Los Angeles College" with your department, program or campus group (e.g., Academic Senate, Media Arts Department, History Circle) when using the statement.

East Los Angeles College gives gratitude and respect to past and present Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people, the original caretakers of this land, whose traditional, unyielded homeland we occupy today on the ELAC campus.

Alternative version

East Los Angeles College honors with gratitude and respect the original caretakers of this land and their descendants, people who today call themselves Gabrieleño, Tongva, or Kizh. We acknowledge the many devastating impacts of repeated waves of settler colonialism wrought upon these people and their ancestors by the Catholic missions, Spain, Mexico, and the United States, who took their homeland by force and deception, including the places our college occupies.

The rich culture, accomplishments, humanity, and continued presence of Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people have too often been ignored, marginalized, and removed from our history and awareness as a consequence of these colonial acts. As an educational institution, we recognize our responsibility to highlight Indigenous histories and advocate for practices, policies, and actions that bring justice for past, present and emerging native communities.

Pronunciation guide:

- Gabrieleño (gab-ree-eh-LAY-nyo)

- Tongva (TONG-va)

- Kizh (KEEch)

These Land Acknowledgements are a step in an ongoing process as our campus works to move forward on issues of equity, humanity, and truthfulness. We hope it will bring a level of recognition to part of the complicated and painful history that our school and its community benefits from. We also hope to call attention to the current and past contributions of people whom our society and education often neglect and try to erase. We by no means think of these statements as the end of this effort. Instead, we sincerely hope that they are a starting point for ongoing movement.

Land Acknowledgements are by their nature flawed and incomplete. They rely on English, a colonial language, and European concepts of territory and borders. More importantly, they cannot correct the wrongs of the past. They can only draw attention and focus purpose for the current moment and future.

Whatever positive effect our acknowledgment has is largely created by you, as you consider your place in this historical and present situation. Will you choose to rethink your existing assumptions or help others to do so? Will you give your attention to the work and voices of displaced people? Will you contribute your time or resources to their current struggles? Will you share your critical analysis of this process to help East Los Angeles College improve?

Learn More and Get Involved

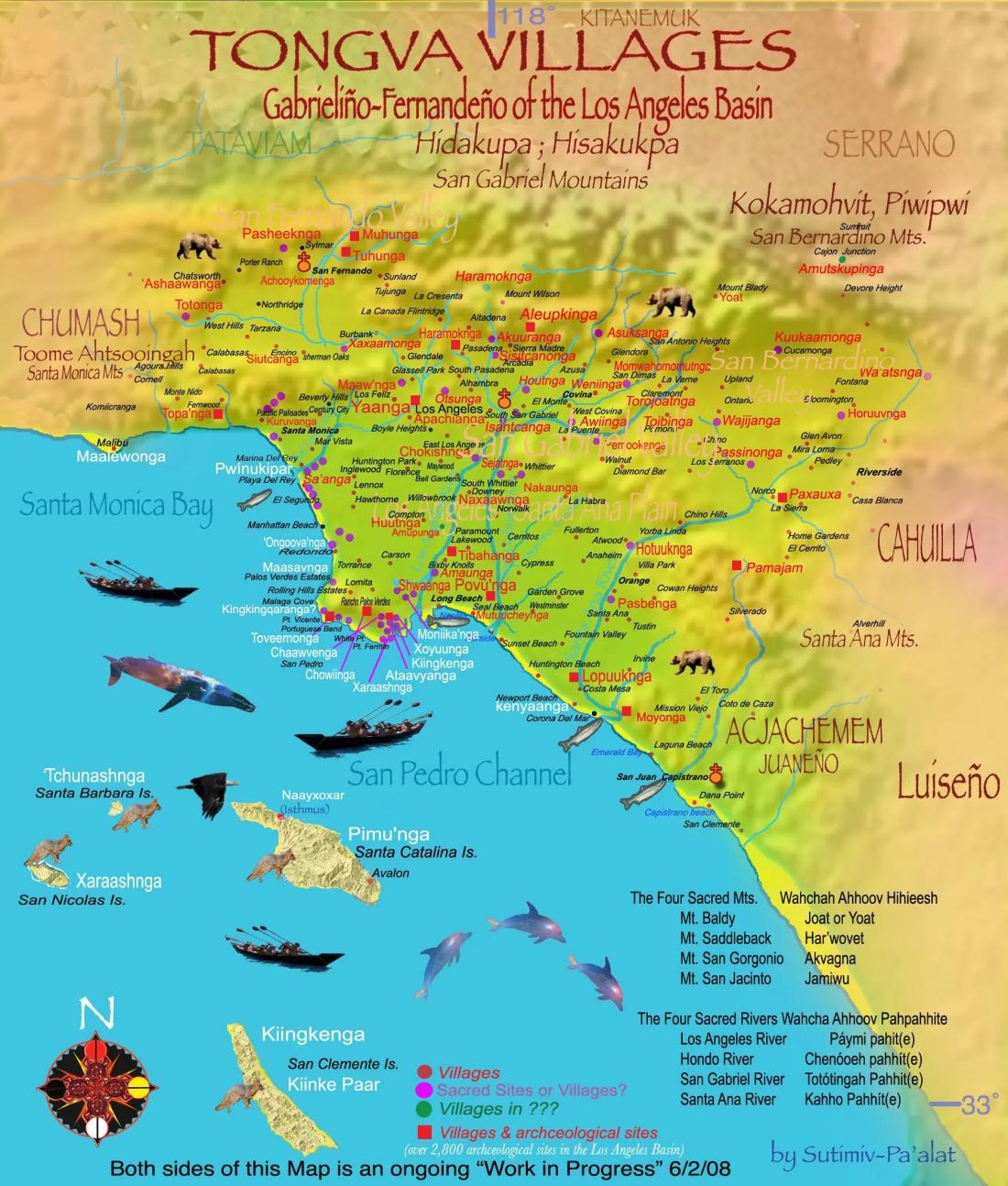

East Los Angeles College, including its Corporate Center in Monterey Park, California and the South Gate Educational Center are located within the traditional homelands of the Gabrieleño, Tongva, and/or Kizh people. Historical sources name the village site closest to ELAC as Apachiangna.

This Acknowledgement should serve as a reminder that the Gabrieleño, Tongva, and/or Kizh people are the original caretakers of the vast region that includes the greater area of the Los Angeles Basin, an area which some contemporary people refer to as Tovaangar. We give gratitude to the Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people as the original caretakers of the land in which we work, live, and learn. We also acknowledge that while various actions of Spanish colonial forces, the Catholic mission system, the Mexican Government, the United States Federal Government and the state of California have dispossessed Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people of their land, they are present and are an active part of our communities and landscape.

Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh History

Native people have inhabited the Los Angeles basin for thousands of years, hunting and gathering wild foods for much of that time and eventually establishing a vibrant network of villages connected through marriage, culture, exchange and a shared Takic language. No traditional term is agreed on for this group as a whole. Historians, ethnographers, and contemporary Indigenous people have applied the names Gabrieleño, Tongva, or Kizh to refer to the Native people who lived in this region. We respect the right of descendants to choose their name, and so we have chosen to include all of these names and to refer to them collectively as Indigenous and/or Native.

In the late 18th century, Spain established 21 missions throughout Alta California. Native Californians endured horrific forms of exploitation and abuse under the Spanish-Catholic mission system in the form of enslavement disguised as essential labor for the construction and maintenance of the San Gabriel Mission (founded 1771) and the San Fernando Mission (founded 1787). Thousands of Indigenous people died at Mission San Gabriel, many from European diseases. The expansion of the Catholic missions under the protection of the Spanish crown diminished much of the traditional resource base, as land was turned into grazing grounds for the benefit of the mission system. Once baptized, “mission neophytes,” as they were called, were not allowed to leave the missions without permission and were forced to live and work according to a directed program of religious and cultural conversion. Many Native Californians actively resisted the missions’ attempt to eradicate their respective cultures and customs in a variety of ways. Among these included an armed revolt against Spanish missionaries over the continuous abuse on Native bodies and land theft in 1785 at Mission San Gabriel led by a baptized chief, Nicholas Jose, and Toypurina, an unconverted spiritual leader who lived in a nearby village. The plot was discovered by mission authorities and eventually crushed, but mission neophytes continued to resist by running away, leading rebellions, or by preserving traditional customs concealed from authorities.

Following Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, the newly formed Mexican government initiated the secularization of Spanish missions that further dispossessed Indigenous people of their ancestral lands. While the new Mexican government declared “Indians” free to move at will, the lands seized by the Mexican government, including the domains of secularized missions were transferred to private citizens as land grants. Following the Mexican American War (1846-1848), the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 ceded California to the United States. While Article I of the Treaty of Guadalupe assured the protection of all people in the annexed territory, in California, the actual outcome was a series of state decrees known as the “eighteen lost treaties” that furthered displaced Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people from their ancestral lands. A proposed treaty to set aside 8.5 million acres of land for Native Californians (1.2 million acres promised to Los Angeles’ Indigenous population) failed to materialize as Californian business interests persuaded the United States Senate to reject and deem the treaties as an “injunction of secrecy.” In 1850, California enacted The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, which legalized the forcible servitude of California Natives and furthermore facilitated their removal and displacement. During the 19th century, American policies contributed directly to the dramatic reduction of Indigenous populations throughout the state of California, which is estimated to have been reduced to 30,000 from upwards of 150,000.

In 1994 the state of California recognized the Gabrielino-Tongva people as the aboriginal tribe of the greater Los Angeles basin. Federal recognition would afford local Indigenous nations the right to self-government and federal benefits, but unfortunately, Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh people have yet to be recognized by the United States Federal Government as one of the 574 Federally Recognized Indian Nations. Today, there are approximately two-thousand Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh descendants living in Los Angeles and the surrounding cities.

Historical Sources and Further Reading

- Mapping Indigenous LA https://mila.ss.ucla.edu/

- Gabrielino Language Resources http://www.native-languages.org/gabrielino.htm

- A Brief History of the Tonga People https://laist.com/news/la-history/a-brief-history-of-the-tongva-people

- Indian Resistance to Mission San Gabriel https://www.kcet.org/shows/departures/mountain-fortress-indian-resistance-to-mission-san-gabriel

- The “Toypurina” Revolt https://www.kcet.org/history-society/the-rebellion-against-the-mission-of-the-saintly-prince-the-archangel-san-gabriel-of-the-temblors-1785

- Federal and State Recognized Tribes Federal and State Recognized Tribes

- California Tribal Communities Link California Tribal Communities

- The Gabrielino, Bruce W. Miller (Sand River Press; Los Osos, California, 1991).

- Yaraarkomokre'e 'Eyoo'ooxono -We Remember Our Land:The Tongva People of present-day Los Angeles County https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/72adcaec1d894f81a06808393afce24f

- LA’s Tongva Descendants: We Originated Here https://www.kcrw.com/culture/shows/curious-coast/las-tongva-descendants-we-originated-here

Connect with Native organizations and movements here

Gabrieleño, Tongva, and Kizh Communities and Organizations

- Gabrielino-Tongva Indian Tribe https://gabrielinotribe.org/

- Gabrieleno (Tongva) Band of Mission Indians https://www.gabrieleno-nsn.us/

- Kizh Nation https://gabrielenoindians.org/

- Chia Café Collective https://www.facebook.com/ChiaCafeCollective/

- Friends of Puvungna (Long Beach, CA): https://www.friendsofpuvungna.org/

Native American Organizations and Action Groups

- Native Organizers Alliance http://nativeorganizing.org/

- Southern California Indian Center https://www.ocindiancenter.org/

- Lakota People’s Law Project https://lakotalaw.org/

- American Indian College Fund https://collegefund.org/students/scholarships/

- National Indian Education Association https://www.niea.org/

- California Native Vote Project https://canativevote.org/

Current Issues Affecting Native Americans:

- Native American Issues Today (2022) https://www.powwows.com/issues-and-problems-facing-native-americans-today/

- Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States

- Protecting Native American History in schools Critical Race Theory and Native American Nations

- Voting Rights Native American Voting Rights Act

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women https://www.csvanw.org/mmiw/

- Challenge to the Native American Child Welfare Act

- HR 1374 (Would criminalize Native pipeline protesters) Lethal force against pipeline protests

- Standing Rock Dakota Access Pipeline (“DAPL”) DAPL Line 3

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women https://www.csvanw.org/mmiw/

Indigenous-centered Arts Organizations

- Native Voices at the Autry https://theautry.org/native-voices/theatre-native-voices

- Meztli Projects, East Los Angeles https://www.meztliprojects.org/about-1

- Native Arts and Cultures Foundation https://www.nativeartsandcultures.org/

- Forge Project https://forgeproject.com/

- Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico: https://iaia.edu/about/

- Indian Arts and Crafts Board: www.iacb.doi.gov

Gabrieleño/Tongva Artists and Writers

- L. Frank Manriquez (Hammer Museum talk)

- Weshoyot Alvitre

- River Garza

- Cara Romero

- Mercedes Dorame

- Kelly Caballero

- Gabrieleno/Tongva Writers https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/tongva-writers-today-the-past-present-and-future-are-unfolding-simultaneously/

- Jessa Calderon

- Frank LaPena and Mark Dean Johnson with Kristina Perea Gilmore. When I Remember I See Red, exh. cat. Crocker Museum of Art, Sacramento, California, 2019. Past exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West: https://theautry.org/exhibitions/when-i-remember-i-see-red

Places to Visit and Respect

- To Be Visible. A Website that includes information on the Tongva, Tongva Art and Cultural Sites, Julia Bogany and more: https://www.tobevisible.org/tongva-art-and-cultural-sites.html

- Kurvungna Springs was once home to a thriving Tongva village. Artifacts and ancestors have been unearthed at the site and these items, along with historical documents, photographs, and other resources, are now on permanent display at the Kuruvungna Springs Nature Center: http://gabrielinosprings.com/wpsite/

- “Tongva Exhibit” at Heritage Park (Santa Fe Springs, CA): https://www.santafesprings.org/cityhall/community_serv/family_and_human_services/heritage/tongva.asp

- “State Parks and Museums Interpreting California Indian Culture and Heritage,” California Department of Parks and Recreation: https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24096

- California Native Plants Digital Garden, Autry Museum of the American West: https://theautry.org/education/digital-tours/california-native-plants%C2%A0digital%C2%A0garden-tour%C2%A0

- Becoming Los Angeles, permanent exhibition at the Natural History Museum Los Angeles. “L.A. Reimagined” by Jessica Porter (accessed May 5, 2022): https://nhm.org/stories/la-reimagined

- LA Starts Here!, permanent exhibition at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes: https://lapca.org/exhibition/la-starts-here/

Dialogues and Presentations

- “Gloria Arellanes oral history interview conducted by David P. Cline in El Monte, California, 2016 June 26.” Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016655427/

- “Solidarity with the Original Caretakers of the Land: Tongva, Ajachemen and Chumash.” Virtual Event dedicated to Indigenous land relations in Southern California, and communal, BIPOC solidarity for others dispossessed from their own homelands (published April 16, 2021): Video, 2:04:55. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3kSV0wsKGLc&t=5049s

- “You are on Tongva Land: Dialogue with Mercedes Dorame, Angela R. Riley and Wendy Teeter.” June 6, 2018. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Video, 1:26:48. https://hammer.ucla.edu/programs-events/2018/06/you-are-on-tongva-land-mercedes-dorame-angela-r-riley-wendy-teeter/